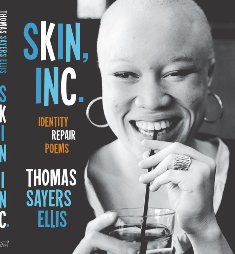

Most poets are still just finding out about their stories in their second books, but Ellis is not most poets. The Maverick Room came in at 121 pages, twice the length of the average collection of poems; so Skin, Inc., which is 181 pages long, might be considered Ellis’s third through fifth books. Raised “in a so-called single parent household in Washington, D.C.,” and educated at Harvard and Brown, Ellis came to national attention as a literary community organizer. With fellow poet and Harvard grad Sharan Strange, he founded the Dark Room Reading Series out of their rented house in Cambridge in 1989. It didn’t take long for the project to outgrow that setting.

The reading series featured African-American writers both hugely successful and secretly influential, from Alice Walker and Terry McMillan to Samuel Delany and Bell Hooks. Word about the readings got around, and soon people were commuting from hours away to attend (including Natasha Trethewey, then a graduate student in poetry at the University of Massachusetts). The series morphed into the Dark Room Collective, a “pre or PMFA” that played a role in the development of award-winning poets as aesthetically diverse as Carl Phillips, Kevin Young, Tracy K. Smith and Major Jackson, and also drew the bright light of publicity from the Boston Globe and The New Yorker. It ran until the late ’90s, its decade-long existence coinciding with the beginning and end of the first major phase of mainstream rap, from the rise of Public Enemy to Jay-Z’s breakthrough.

While everything around Ellis was blowing up, in the hip-hop sense of the phrase, he took his time with his poems. The ones in his chaplet The Good Junk (1996) and his chapbook The Genuine Negro Hero (2001) have more in common with the self-knowing work of Ellis’s Nobel laureate teachers Seamus Heaney and Derek Walcott than with platinum recording artists. The music in them is played by people, not CD players. “Sticks” starts out as a disconcerting family romance (“I learned to use my hands watching him/Use his, pretending to slap mother/When he slapped mother”), but rather than closing with catharsis and confrontation, the poem ends with an uncertain resilience in which the pain—the narrative—is channeled into writing and drumming:

While everything around Ellis was blowing up, in the hip-hop sense of the phrase, he took his time with his poems. The ones in his chaplet The Good Junk (1996) and his chapbook The Genuine Negro Hero (2001) have more in common with the self-knowing work of Ellis’s Nobel laureate teachers Seamus Heaney and Derek Walcott than with platinum recording artists. The music in them is played by people, not CD players. “Sticks” starts out as a disconcerting family romance (“I learned to use my hands watching him/Use his, pretending to slap mother/When he slapped mother”), but rather than closing with catharsis and confrontation, the poem ends with an uncertain resilience in which the pain—the narrative—is channeled into writing and drumming:

The page tightened like a drum

Resisting the clockwise twisting

Of a handheld chrome key,

The noisy banging and tuning of

growth.

Throughout these early poems, drums figure as a means of escape and entrapment (snare). “A Baptist Beat” conflates a go-go performance with a church service (“The tambourine shakes like a collection plate”), while “Tambourine” inverts the simile (“Sundays, it took a sinner’s beating”). Ellis addresses the cowbell that called the neighborhood to clubs and block parties, but also families during blackouts: “Down-to-earth, hardheaded, hollow, loud./I know your weak spots. You know mine.” This conflicted sense of the sources and meanings of rhythm is personified in “Tambourine Tommy,” the story of a local character just this side of St. Elizabeths who showed up at events with tambourines and bells strapped to his body. Ellis is aware of the comedy and pathos in the situation, but he leaves the reader with solidarity in suffering: “the way/He beat himself/(head, shoulders, knees/and toes), proved he//Was one of us.”

The Maverick Room shuffles the chapbooks’ personal poems with newer poems about the outsize personalities clustered around musician-impresario George Clinton and his bands Parliament and Funkadelic. A reader could have worried that the abrupt change of subject matter from local characters to famous musicians would deprive Ellis of the lived intensity his poems thrived on. That reader’s worry would have been misplaced. The book opens with an ode to Garry Shider, the voice at the beginning of Parliament’s Mothership Connection, better known as Starchild. Ellis writes:

Newborn, diaper-clad, same as a child,

That’s how you’ll leave this world.

No, you won’t die, just blast off.

The diaper, the spaceship: Shider’s iconography was crazy, and also a way of reminding the audience of funk’s origins, not Saturn but a similarly alien place somewhere near the gut. Four stanzas later, after Shider blasts off and the “black hole at the center/Of the naked universe” responds, Ellis riffs on one of Parliament’s best-known songs to set the stage for his own arrival, “Roofs everywhere cracking, tearing,/Breaking like water.”

As poetic births go, The Maverick Room was promising: personal but not private, accessible but not obvious. The risks of reclaiming the Clinton universe from within the heart of the Bush II era paid off. Both enormously successful and incorrigibly idiosyncratic, P-Funk smuggled the pleasures of bop back into dance music while underscoring a message that deserves to be called hilarious, positive and above all autonomous. Following their lead, Ellis teased his audience while expanding his personal mythology. And the influence of P-Funk’s over-the-top portmanteau titles, such as “Gloryhallastoopid” and “Psychoalphadiscobetabioaquadoloop,” had the liberating effect on Ellis’s aesthetic predicted in the title of Funkadelic’s 1970 album, Free Your Mind… And Your Ass Will Follow.

At the same time, the don’t Ellis uttered in “Marcus Garvey Vitamins” as a dare—”Don’t like it”—fulfilled its purpose: the book is sui generis, a record of Ellis’s experiences and excitements, not a labor at the service of literary history. As he says in “Balloon Dog (1993),” “poetry escapes/poems that/contain more//ego than/feeling.” It’s unclear whether this poem loves or hates its insight that a poem might be something like a rubber tube, filled with hot air, twisted ingeniously, a solid scribble. This is a signal moment of the poet articulating his resistance to other people’s rules for what a poem has to be: poems are almost never going to be permanent, so stop worrying about that. But the poem at hand better have enough whatever to fill the form into a specific, recognizable shape. Call it empathy: “Nothing,/not even//love,/should have to live up to/or as long as//sculpture’s attempted/permanence.”